This week’s course focused on Access to Medicines. The presenter was lawyer Rachel Kiddell-Monroe. (Her complete presentation is available here.)

Yale and HIV Drugs

In 2001, Doctors without Borders (or Médecins sans Frontiéres, MSF) approached the pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) to ask for a cheaper generic version of their HIV drug, d4T. The drug was available in developed nations for $1,600 per year per patient. However, MSF was trying to work in South Africa, and needed the drug to be affordable to make a real impact. BMS refused the request, saying that they required the money to support research and development of new HIV drugs.

So MSF went to the source. A professor at Yale University, William Prusoff, was the discoverer of the d4T treatment. As is common practice, the university had sold the d4T licence to BMS, allowing them to distribute the product as they wished. It is for this reason that Yale, too, decided it could do nothing for MSF. Its hands were tied.

Enter students. Groups of students at Yale University organized in protest. After all, their tuition money was the reason that Prusoff was able to discover d4T in the first place. Professor Prusoff was also upset and wrote an editorial in the New York Times stating his position that, “d4T should be either cheap or free in sub-Saharan Africa.”

At this point, BMS was aware of the negative publicity over the subject and changed their decision. Within a year the cost of d4T for South Africa was reduced by 96%.

The drug d4T is no longer the preferred treatment for HIV in developed nations. However, in developing nations it is still part of the typical cocktail of drugs – thanks in part to its affordability.

Access to Medicines

It is estimated that 2 billion people in the world lack access to life-saving drugs – that is one third of the world’s current population. In sub-saharan African, about half of the population lacks access.

But lack of access to medicines is caused by many factors. As we see above, a major factor is Affordability, but of equal importance are Availability and Appropriateness. Let us look at each of these separately.

Affordability

In 1995 an international agreement was made, called TRIPS, that required the honouring of international patents (some countries, e.g. Brazil, did not allow patenting of pharmaceuticals). The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) “establishes minimum levels of protection that each government has to give to the intellectual property of fellow WTO members.”

In one fell swoop, the agreement (as of 2005) ended any manufacturing of generic drugs for cheap, local distribution, and increased the profits of patent-holding pharmaceutical companies.

There have been cases where governments cannot afford to provide medicines for the needy in their country. These countries knowingly broke the TRIPS agreement to provide adequate medicines for their citizens. Some in return, as is the case with Thailand, were penalized via trade barriers with the United States. The Abbott drug company even withdrew its pharmaceuticals from the country.

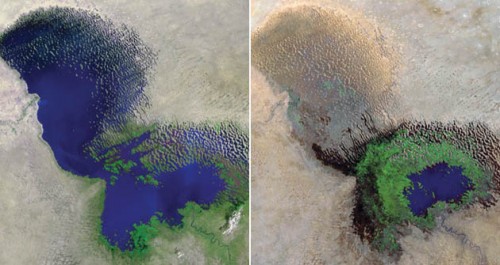

Availability

The medicine needs of the developing nations differ from those of the developed nations. For example, malaria barely affects the developed nations, whereas a malaria medicine is greatly needed in some developing nations. This is true for many other diseases, dubbed Neglected Diseases.

But drug companies refuse to create new and/or improve old drugs for these diseases. The financial incentive is not there. What results is the use of old medicines with terrible side effects or even attempts to use animal formulas. Failing even these last-ditch efforts, the only course is simply NOT treating patients.

Appropriateness

Rachel Kiddell-Monroe was working with MSF in Rwanda. She was touring a local hospital when she was brought to a barred-off wing. Her inquisition into what was behind the barricade gave her this answer: people waiting to die. The patients behind the barricade were mostly HIV patients (without a proper diagnosis). She was struck by the knowledge that if these people were in one of the developed nations they would not be dying. Instead they would have access to the medicine they needed and would probably be leading normal lives. But all Rachel could do, along with the help of her crew, was sit with these people, holding their hands, so they could die with dignity.

The issue in this case was a lack of appropriateness of the HIV drugs that had been created. Even if they could have been afforded, they would not fit the needs of the population. Most times the drugs make some requirement, e.g. that you take them with meals, three times a day. If you have no access to three meals of food, or even necessary drinking water then the drug may not work or even show adverse effects.

Drugs, like so many other things, needs to be created with a context in mind.

Hopeful Future

In 1999 Médecins Sans Frontiéres won the Nobel Peach Prize. With the money from the prize the organization started the initiative Access to Medicines. That initiative lead to the availability of the d4T drug mentioned previously, and continues to be a major player in providing medicines to those who need them.

Universities have also continued to play a leading role in universal access to medicines. The group Universities Allied for Essential Medicines (UAEM) aims to:

- promote access to medicines for people in developing countries by changing norms and practices around university patenting and licencing

- ensure that university medical research meets the needs of the majority of the world’s population; and

- empower students to respond to the access and innovation crisis.

The Access to Medicines debate isn’t just a hope for headache-remedying Tylenol, it is an issue of life and death. And life that is not just the avoidance of death but the opportunity for a truly meaningful existence.

Dear whoever is interested,

Dear whoever is interested,